On August 30, 2010, John T. Williams, a Native American woodcarver, was walking down a Seattle street with a carving knife and a piece of wood when he was fatally shot by Seattle Police Officer Ian Birk. The shooting ignited a firestorm of controversy, highlighting issues of police brutality, use of force, and implicit bias in law enforcement. Williams' story is a tragic one, but it also serves as a powerful reminder of the ongoing challenges we face as a society in holding police accountable and ensuring justice for victims of police violence. This article explores the story of John T. Williams, from his artistic background to the circumstances surrounding his death, and the impact his legacy has had on police reform efforts in Seattle and beyond.

1. Introduction to John T. Williams and the shooting incident

Who was John T. Williams?

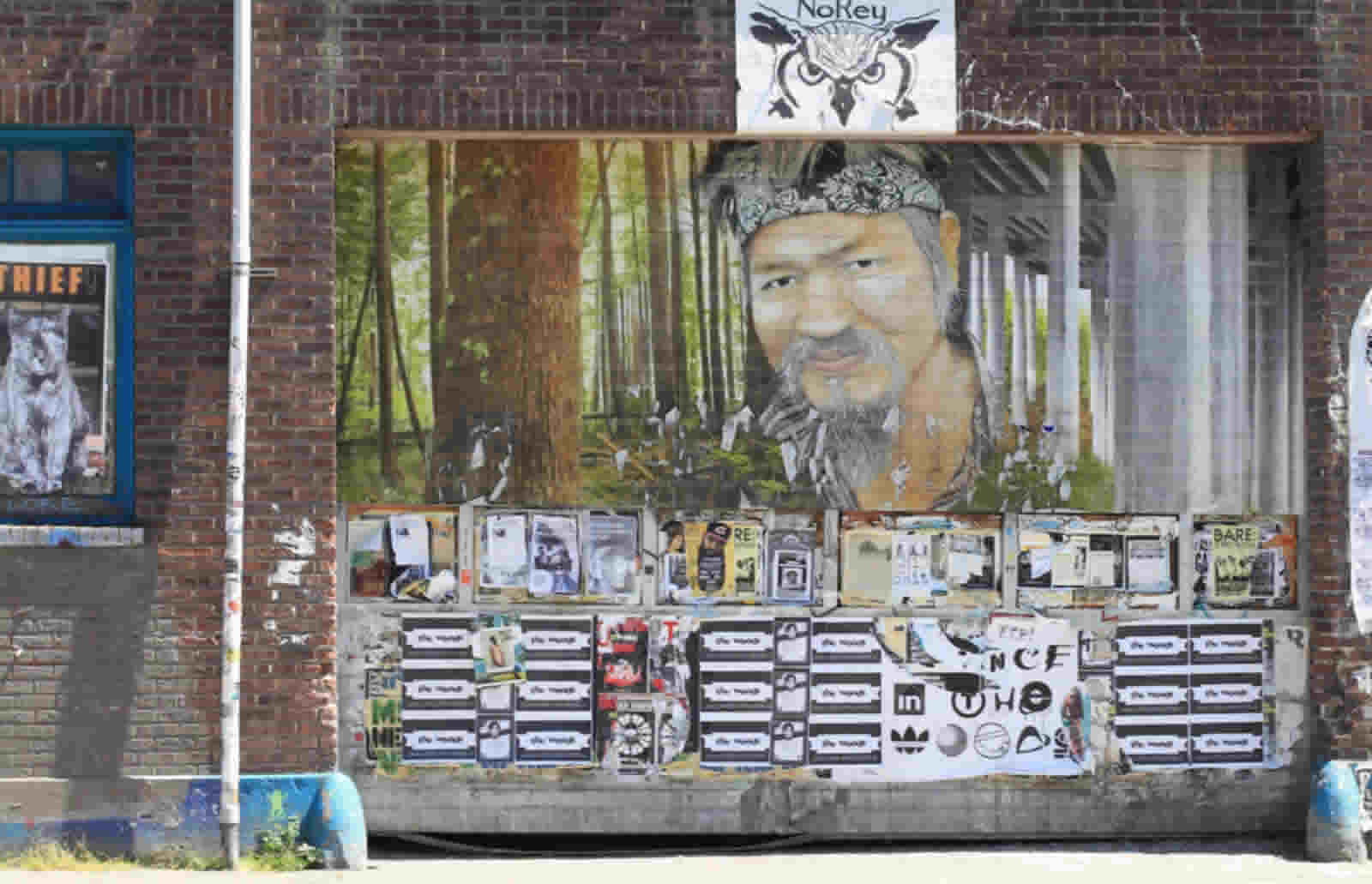

John T. Williams was a Native American woodcarver of the Nuu-chah-nulth tribe from British Columbia, Canada. He spent most of his life in Seattle, where he was well-known for his intricate and beautiful carvings.

Overview of the shooting incident on August 30, 2010

On August 30, 2010, Williams was walking down a street in downtown Seattle while carrying a small carving knife and a piece of wood. Seattle Police Officer Ian Birk stopped his patrol car and ordered Williams to drop the knife. Williams appeared to be deaf in one ear, and it is unclear whether he heard Birk's command. After Williams did not drop the knife, Birk fired four shots, killing Williams. The incident was captured on video and sparked widespread outrage and controversy.

2. Williams' artistic background and passion for carving

Williams' childhood and artistic influences

Williams' father was also a woodcarver, and Williams grew up watching and learning from him. He was also influenced by the traditional Native American carvings he saw during his childhood visits to British Columbia.

His love for traditional Native American carving

Williams' carvings were influenced by the traditional Native American art of the Pacific Northwest, known for its intricate designs and depictions of animals and spirits. He made carvings ranging from small figures to towering totem poles.

How Williams' passion for carving intersected with his experiences of homelessness and poverty

Williams struggled with homelessness and poverty for most of his life, but he continued to carve and sell his art on the streets of Seattle. His carvings were a source of pride and income, and he often spoke about their importance to him and his heritage.

3. The confrontation with Seattle Police Officer Ian Birk

Overview of the encounter between Williams and Birk

Officer Birk claims he saw Williams carrying a knife and initially pulled over to warn him about the dangers of carrying such a weapon. But when Williams didn't immediately drop the knife, Birk felt threatened and fired four shots, killing Williams.

Analysis of the events leading up to the shooting

The circumstances leading up to the shooting are unclear, as there were no witnesses and Birk did not activate his dashboard camera. Williams had a history of alcoholism and homelessness, and some have suggested that Birk may have targeted him due to implicit bias against Native Americans.

Questions of police training, use of force, and implicit bias

The shooting of John T. Williams sparked widespread controversy and raised important questions about police training, use of force, and implicit bias. It also led to changes in the Seattle Police Department's policies regarding encounters with individuals who appear to be in crisis.

4. Eyewitness accounts and controversy surrounding the shooting

Testimonies from witnesses present during the shooting

Several witnesses who were present during the shooting disputed Birk's account, claiming that Williams did not pose a threat and that Birk fired without warning or provocation.

Media coverage and reactions from the Seattle community

The shooting of John T. Williams received widespread media coverage and sparked protests and demonstrations in Seattle. Many in the Seattle community were outraged by the shooting and called for justice for Williams.

Controversy surrounding the initial investigation and charging decisions

The investigation into the shooting was controversial, as the initial decision not to charge Birk with a crime was met with widespread criticism. Ultimately, Birk resigned from the Seattle Police Department and was charged with second-degree murder, but he was acquitted by a jury in 2012. The shooting of John T. Williams remains a controversial and tragic incident in the history of Seattle's police-community relations.2>

The importance of holding law enforcement accountable for their actions

The tragic events of August 30, 2010, highlighted the critical need for police accountability and reform in Seattle and beyond. The shooting of John T. Williams was a clear example of the devastating impact that police brutality can have, not only on the victim but also on their loved ones and the community at large.

The ongoing struggle for justice and change

Despite the significant steps taken towards police reform in Seattle, there is still much work to be done. The fight for justice and accountability continues, with ongoing challenges that need to be addressed. It is the responsibility of all members of society to work towards a fair and just system that values the lives and basic human rights of all individuals.

The power of community action

The movement for police accountability and reform in Seattle was driven by the persistence and dedication of community advocates and activists who refused to accept the status quo. Their unwavering commitment to justice played a crucial role in highlighting the systemic issues faced by marginalized communities and pushing for meaningful change. The legacy of John T. Williams serves as a reminder of the power of community action and the importance of continuing to fight for progress.The story of John T. Williams is a heart-wrenching reminder of the work we still need to do to ensure police accountability and address systemic issues of racism and bias in our society. But his legacy also inspires hope and underscores the power of activism and community organizing in driving meaningful change. By learning from Williams' story, we can continue to push for a more just and equitable future for all.

FAQ:

What were the consequences of the shooting for Officer Ian Birk?

Officer Ian Birk was fired from the Seattle Police Department following an internal investigation. However, he was not charged with a crime, and the King County prosecutor declined to bring charges against him. Birk later challenged his firing and was awarded a settlement of $100,000.

What changes have been made in response to the shooting and the subsequent outcry?

The shooting of John T. Williams sparked a wave of public protests and calls for police reform in Seattle. In response, the Seattle Police Department implemented a number of changes, including new use of force policies, enhanced community policing efforts, and increased accountability measures. The city also established a Community Police Commission to oversee the department's reforms and ensure community input.

Why did John T. Williams carry a carving knife?

As a traditional Native American woodcarver, John T. Williams often carried a carving knife with him in order to work on his projects throughout the day. Despite this, Williams was not seen as a threat by those who knew him and had no prior history of violence.

What is the ongoing impact of John T. Williams' legacy?

John T. Williams' death continues to be an important touchstone in discussions around police accountability and reform. His story has prompted many to question the use of force by law enforcement, particularly in situations where mental illness or disability may be a factor. Williams' memory also lives on through the John T. Williams Totem Pole, a memorial carving erected in his honor in Seattle's Occidental Park.

______________________________

John T. Williams, a 50-year-old seventh generation Nitinaht carver of the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations, was shot four times by a Seattle police officer on August 30, 2010. He died at the scene. His only crime appears to have been walking across the street carrying a carving knife and a chunk of cedar.

In a press conference the day after the shooting, Seattle Police Department (SPD) Deputy Chief Nick Metz said that Officer Ian Birk, 27, who has been with SPD for two years, was stopped at a downtown Seattle traffic light at 4:15 p.m. when the woodcarver crossed the street in front of his marked police car carrying an open pocketknife and a telephone-book-sized piece of cedar. “And he could see the knife,” Metz told reporters, “the blade of the knife, and he could see he was doing something to the board. The officer thought it was important to find out what was going on and why this person had in public an open-blade knife.” Metz said Birk got out of his car, approached Williams from behind and ordered the woodcarver to drop the knife three times. When Williams failed to do so within four seconds, Officer Birk fired his weapon five times from a distance of 10 feet. Williams was struck by four bullets, including one lethal shot to the chest wall, and died at the scene. In its initial statement to the press, SPD described Williams as having been “advancing towards” Officer Birk, who felt threatened and responded by firing his weapon.

Over the next few days, eyewitnesses began stepping forward to dispute this version of events, and the police department quickly retracted its statement.

At a press conference on September 4, 2010, at the Chief Seattle Club, a day-shelter for Natives where Williams was a familiar face, Jenine Grey, the club’s executive director, held SPD accountable for the death. “We are angry and outraged that his life was interrupted for seemingly no reason, and so callously disregarded. We are worried about our most vulnerable community members, who suffer regular harassment and abuse on the streets of Seattle.”

The shooting—and the fact that SPD’s attempts at damage-control included referring to the victim as a “chronic inebriate” with a “rap sheet”—has galvanized Seattle’s Native community and its allies, prompting a groundswell of diverse organizing efforts in response to the killing. Many think this could be the Native community’s “Rodney King moment,” a reference to a brutal—and videotaped—beating of a black motorist by Los Angeles police officers in 1991 that made national headlines for months and galvanized activists in Los Angeles, who pushed through reforms of the Los Angeles Police Department. There is a burgeoning awareness of the problematic relationship between SPD and communities of color, especially with street Natives such as Williams who have regular contact with police, and are frequently harassed and arrested for offenses inextricably linked to being homeless, such as drinking and urinating in public.

The shooting—and the fact that SPD’s attempts at damage-control included referring to the victim as a “chronic inebriate” with a “rap sheet”—has galvanized Seattle’s Native community and its allies, prompting a groundswell of diverse organizing efforts in response to the killing. Many think this could be the Native community’s “Rodney King moment,” a reference to a brutal—and videotaped—beating of a black motorist by Los Angeles police officers in 1991 that made national headlines for months and galvanized activists in Los Angeles, who pushed through reforms of the Los Angeles Police Department. There is a burgeoning awareness of the problematic relationship between SPD and communities of color, especially with street Natives such as Williams who have regular contact with police, and are frequently harassed and arrested for offenses inextricably linked to being homeless, such as drinking and urinating in public.

However, this incident is just the most recent in a string of clashes between minorities and SPD officers that have increased the tension between the city’s police and many of its residents. SPD Officer Shandy Cobane was caught on video in April 2010 stomping on the head of a prone Latino suspect after telling him that he would, “beat the fucking Mexican piss out of you, homey. You feel me?” The announcement in December that neither the King County Prosecuting Attorney nor Seattle City Attorney would file charges against Cobane was met with outrage and frustration. “These problems in the Seattle Police Department have been going on since the 1960s and 1970s, and they haven’t changed much in the atmosphere for minorities and Native Americans,” said longtime Seattleite and Cowichan First Nations member Abe Johnny, a veteran of the 1970s-era Indian fishing wars who coordinated security at the vigils and protests that took place outside the King County Courthouse throughout the week of the inquest for the Williams case.

King County Executive Dow Constantine ordered an expedited inquest into the killing after SPD’s internal Firearms Review Board found that the shooting of Williams was unjustified (the details of the board’s investigation have not been made public). Inquests are fact-finding hearings conducted before an eight-member jury, routinely called to determine the causes and circumstances of any death involving a member of any law enforcement agency within King County. It was convened January 10.

The jury, after hearing six days of testimony by witnesses and experts, deliberated for nine hours, then gave their findings to Judge Arthur Chapman. The six men and two women on the jury answered 13 questions, known as “interrogatories to the inquest jury.” The first was, “On August 30, 2010, did Seattle Police Officer Ian Birk observe John T. Williams crossing the street?” All eight jurors answered “yes.” Just one of the eight jurors answered “yes” to the crucial question, “Based on the information available at the time Officer Birk fired his weapon, did John T. Williams pose an imminent threat of serious physical harm to Officer Birk?” Only four of the jurors were convinced that, “Officer Ian Birk believed that John T. Williams posed an imminent threat of serious physical harm to Officer Birk at the time Officer Birk fired his weapon.”

The family also had to watch police dashboard-camera video footage of the mortally wounded Williams lying for several minutes before being approached by a “tactical line” of officers, who handcuffed him before offering medical assistance. And they were shown blown-up images of their family member on the autopsy table—including a photograph of his bullet-ridden heart in a tray, which prompted the family to walk out of the courtroom.

Many facts were presented in the inquest, but none of them explained why Birk shot Williams with so little provocation. It was established that there had been no citizen complaints against Williams that would help to explain why the officer initiated contact with Williams, and no witnesses saw Williams behaving in a threatening manner; in fact, two eyewitnesses described Birk as the aggressor. It was also evident that Birk never identified himself as an officer of the law—the witness nearest to the shooting testified at the inquest that she heard Birk yelling, but ignored it as a common occurrence on a downtown street. “If I had heard ‘Stop! Police!’ I would definitely have stopped and turned around,” she stated on the witness stand. As documented in his patrol car’s camera footage, Birk fired his weapon within four seconds of issuing the commands for Williams to drop the knife. The bullets struck Williams’s right side, indicating that he was not facing the officer at the time of the shooting. Found close to the scene was William’s three-inch pocketknife—shorter than the legal limit for a blade in the city of Seattle—that he used for carving.

“The purpose of the inquest is to air the facts,” stated Judge Chapman at the start of the deliberation, but some people who attended the inquest did not feel that it served this function adequately. For reasons that are mysterious to the Williams family attorneys, the jury was not allowed to hear testimony that the late Williams was deaf in one ear and hearing-impaired in the other. Nor was the jury allowed to see photographs of Williams and other family members carving in public, which would have underscored the point that carrying and using knives in public was habitual and customary for this clan of seventh- and eighth-generation First Nations carvers who have work in the collections of the Smithsonian and the Royal BC Museum in Victoria, British Columbia.

Still, Ford, the civil rights attorney representing the Williams family, said of the outcome: “I believe that this is about as strong a statement as you can expect.… in all the contested questions, there’s a significant majority [of jurors] that says, ‘This was not justified.’?”

King County Prosecuting Attorney Dan Satterberg will take the inquest jury’s findings—and SPD Firearms Review Board’s earlier “unjustified” shooting verdict—into consideration in deciding whether to press criminal charges against Birk, who was stripped of his gun and badge after the Firearms Review Board’s finding, and has been on paid leave since the shooting. The family of John T. Williams and a throng of supporters visited Satterberg’s office January 21 to urge the attorney to file criminal charges. Ahousat First Nations member Pat John was one of the supporters who accompanied the Williams family; John, who said he was “uplifted” by the visit, drummed and sang a prayer song for Satterberg. “He knows there is a task there and promised we will know his decision by February 15 or thereabouts,” John said.

The prosecutor’s office will consider whether to charge Birk with second-degree murder, first-degree reckless manslaughter or second-degree negligent manslaughter—or may choose to not charge him at all. While the findings of the inquest jury were damning according to the Williams’s attorney, in the 30 years that King County has had its current inquest system, an inquest has never led to charges filed against an officer—even when there had been Firearms Review Board findings to the contrary. A second-degree murder charge would require showing beyond a reasonable doubt that Birk intended to unlawfully kill Williams, or that Birk intentionally and unlawfully assaulted Williams, causing his death. Experts agree that either would be difficult to prove.

Amidst this shattering tragedy, some found reason for hope. The community came together and organized support for the Williams family during the inquest. The nearby Chief Seattle Club became a refuge, opening its dining room each day to the Williams family and their supporters for a lunch followed by song, prayer and the burning of sage—a symbolic purification ritual common to many of the members of the diverse array of Native supporters.

Ho-Chunk Nation member Penny Octuck-Cole, who attended the inquest, said the courtroom was filled everyday with a multicultural group of supporters. “I witnessed and experienced the true meaning of synchronicity,” she said. “All four colors of man—the medicine wheel—came together to support the Williams family and to speak out for justice!”

That justice may have to come from the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ), which has opened a preliminary review of SPD’s practices after the American Civil Liberties Union of Washington and dozens of community groups asked for an investigation into SPD’s use of force against minorities. In response to the announcement of the DOJ review and the conclusion of the inquest, Blackfeet member Gyasi Ross, who also attended the inquest, said “We’re thankful to the jurors for seeing past Ian Birk’s attorney’s attempts to obscure the issue and put John T. Williams on trial, attempting to paint John T. Williams as ‘just another drunk and belligerent Indian.’ But ultimately, our true ‘win’ comes from an investigation from the Department of Justice into why this happened, and also from making sure that it never happens again to anybody, Native or non.”

He's the coward Ian Birk and his bully cop friends. Watch these cowards as they approach one of our fallen warriors after he was shoot four times. He's dieing and they just sat there.

Here's a second dash board camera.